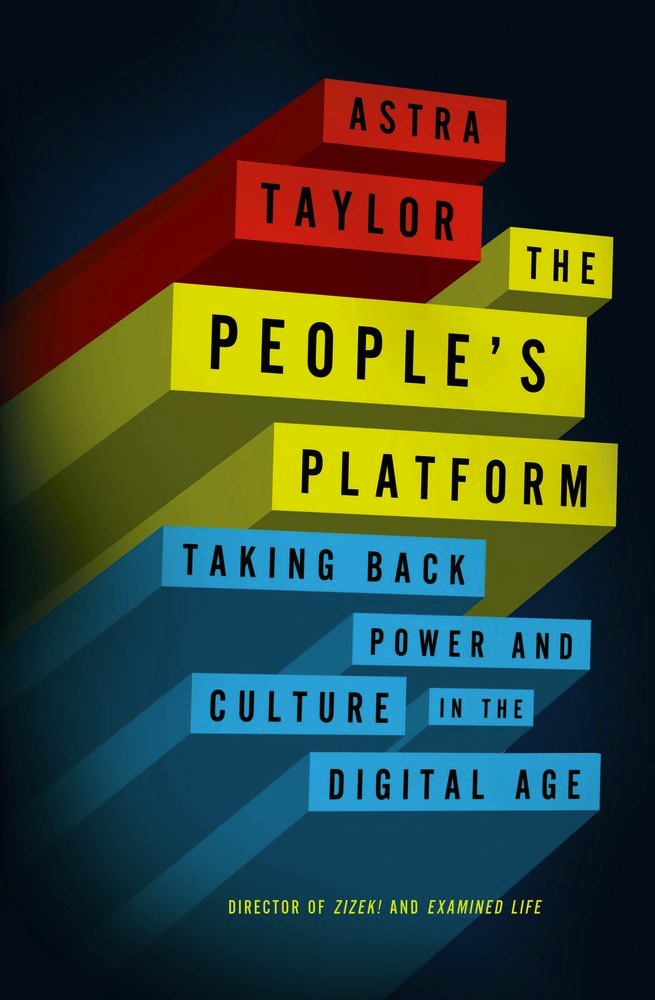

Filmmaker Astra Taylor’s new book, The People’s Platform, propounds that the Internet has failed to bring about the great leveling that some of its apostles foretold but has instead concentrated power in fewer hands than ever before.

FILMMAKER ASTRA TAYLOR

SEES DOOMY FUTURE FOR

INDEPENDENT THOUGHT

Forerunner of Voice of Baltimore

cited as ‘best of both worlds’

By Stephen Janis

It is a ritual that extends as far back as the Frankfurt School and Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936). A new technology appears to transform the way we live, think, and make a living in a mostly productive capacity.

That is, until a critic, in this case Benjamin, looks under the hood and generates a critique that calls into question all the casual assumptions that drive our understanding of it.

Which is where Astra Taylor enters with her new book, The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age.

She too, like Benjamin, sees politics at play in our digital transformation where others see solely utopian potential. And like Benjamin, she constructs a critique that illuminates how the same process of self- interest that drives development of new technologies can also unravel its best attributes.

Taylor accomplishes this by giving us a true and well-articulated sense of the potential for heightened inequality that naturally emerges from the ashes of transformative change, and how that very idea is tinged with a sense of defensive near-fanaticism that protects the unequal distribution of the benefits.

This is, of course, the dilemma that Taylor and others like her, face. Are we instruments of technological determinism, or free actors who can keep at least a palpable democratic footing in the cybersphere?

Are we participants in the dawn of a new era of total information, or so-called digital serfs toiling away creating a free stream of content for zillionaires like Mark Zuckerberg to monetize?

It’s a dilemma that propels Taylor’s strongest argument. She, like Benjamin, understands that technology is not a neutral tool. She also conveys, like old-school cultural theory superstar Raymond Williams, that technological determinism is a convenient way of disguising the underlying social injustice that arises when any technology radically alters the playing field.

She makes the most coherent argument yet that the most interesting aspect of the Internet is how familiar it really is, and how tethered it is to the existing hierarchies and economic inequalities of the tactile world it was once touted as destined to transcend.

Particularly in the realm of media is where Taylor makes her most insightful arguments.

The proponents of “free,” fail to mention how they have mined the paths of “free” communication with hidden tolls that discretely gather our personal information to be sold, exploited or otherwise re-purposed later.

Astra Taylor is a documentary filmmaker, writer & activist whose work has appeared in The Nation, the London Review of Books, n+1 (a New York- based American literary magazine), The Baffler, and other publications.

It’s akin to a digital public square fortified as a sort of electronic Trojan horse. We are deluded with the promise of free, only to unwittingly allow billionaires to track our friendships, reading habits, and even the content of our emails.

Taylor does find bright spots. Among them, local watchdog news website Investigative Voice, which she extolls as “the best of both worlds.“ [Full disclosure: She interviewed Janis for the section; he was the content director for the site.]

“For a time,” Taylor says, “it was a shining example of what many hoped our new media future would be. It combined the best of the shoe leather journalism and exploited the Internet as a quick and affordable distribution platform.”

She also lauds the efforts of the Occupy Wall Street movement, which she has written extensively about, to deploy social media for rallying to a movement that had a marked affect on the country’s political consciousness.

But still, following Taylor’s argument conjures up a stunning big-picture sense of what we’re ultimately missing: we are in fact living in the so-called platform era. That is, all the wealth, cultural currency and political capital has accreted to the people building the tollways of the Internet.

It makes sense when you read Taylor’s account of her own struggle making a ground-breaking series of documentaries on philosopher Slavoj Žižek or other artists she interviews who can’t get paid for their work. It is this allocation of resources to infrastructure that directs the willful imbalance of the Internet spoils. All the profit motive is engaged and pursuing parasitical demands.

Google monetizes content for which it spends nothing to create. Similar with Facebook and the other so-called “media giants” where we make the marrow of their fiscal bones. A close reading of Taylor magnifies the argument that these companies are nothing more than facile plays at passive exploitation. You make the content, and we get paid.

This is the departure point for Taylor for a proactive and far reaching appraisal of this apparently zero sum game. She argues eloquently and with effectively arrayed sources that there needs to be discussion.

sjanis@gmail.com

Editor’s note: Stephen Janis founded the award-winning Investigative Voice watchdog news website in 2009, which continues today as Voice of Baltimore. He is currently an investigative producer for WBFF Fox45-TV, where he has been nominated for and won Emmy awards for television excellence the past three years.