Former Baltimore Sun reporter and Maritime Editor, FMC Chairman and Congresswoman Helen Delich Bentley, shown here at her 90th birthday celebration in Nov. 2013. (VoB File Photo/Bonnie Schupp)

THE FORMER CONGRESSWOMAN

AND CHIEF CHEERLEADER

OF THE PORT OF BALTIMORE

DIED SATURDAY AT AGE 92

The son of a bitch who caused it!

Feisty to the end, and checking out on her own terms, former Baltimore Sun reporter and Maritime Editor Helen Delich Bentley died Saturday at her home in Lutherville, where she had been in hospice care for more than a month.

The five-term congresswoman and staunch advocate of the Port of Baltimore, whose bi-weekly shipping column was once syndicated in more than 200 newspapers, was 92.

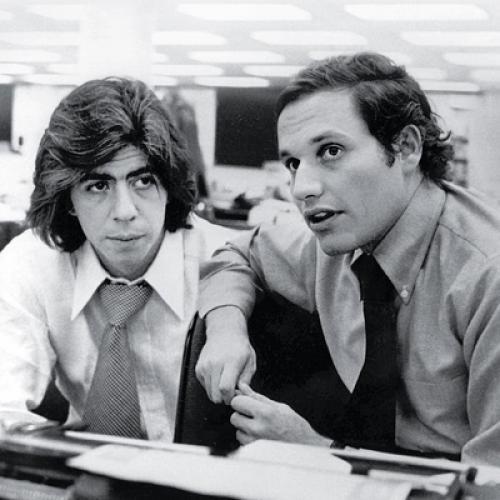

At a Baltimore Sun reunion lunch five years ago, retired Night Editor and former rewrite man Dave Ettlin asked Bentley about her infamous streak of four-letter words on a ship-to-shore telephone in 1969 that caused the Federal Communications Commission to abruptly cut her off the air, an incident which made headlines round the world and embarrassed then-President Richard Nixon, who, with much hoopla, had just appointed her Chairman of the Federal Maritime Commission but then refused to swear her in at the Oval Office.

Bentley gleefully described the incident to Ettlin (who was not on rewrite the night of its occurrence), but then pointed a finger at the former Sun reporter and rewrite man who was — AL Forman, now the Managing Editor of Voice of Baltimore — with the admonition, “And there’s the son of a bitch who caused it!”

She was only half-kidding, of course: Bentley was never one to mince words. But she had mellowed in her old age, and had actually begun to use such language as “please” and “thank you,” niceties that were unknown to her throughout her professional life, where she attained praise and notoriety for being crusty and tough.

It was central to her success: She fought her way to the top in professions — newspaper reporting, television and the maritime industry — that were virtually closed to women when she started out. She quickly recognized that the only way she could get ahead in that so-called “man’s world” was to be as tough as nails — and to cuss like a longshoreman.