Poet Shirley Brewer, right, reads from her chapbook, After Words, at scene of fatal stabbing of Johns Hopkins research assistant Stephen Pitcairn on the third anniversary (July 25, 2013) of his death in 2010, as Charles Village friends and neighbors look on. (VoB Photo/Bonnie J. Schupp)

BALTIMORE POET SHIRLEY BREWER

SPEAKS IN VOICE OF MURDER

VICTIM STEPHEN PITCAIRN

Johns Hopkins researcher stabbed

to death in Charles Village in 2010

POEMS PUBLISHED BY APPRENTICE HOUSE

By Sara Heilman

Shirley Brewer sat in her green “writing chair,” a piece of furniture that didn’t have a snowball’s chance of standing out among the eclectic décor of the Baltimore poet’s homey living room in Charles Village.

Brewer’s third-floor apartment was more comforting than the crisp autumn air outside… but it wasn’t the weather that was leaving chills that day.

Instead, it was Brewer’s story of how her chapbook, After Words, came to be published after 23-year-old Johns Hopkins University researcher Stephen Pitcairn was murdered three-and-a-half years ago just a block south of her Northeast Baltimore home.

Brewer’s After Words — a collection of poems revolving around Pitcairn’s murder — resonated with the grief-stricken Charles Village neighborhood, as well as the Pitcairn family.

Brewer, who is from Rochester, N.Y., had a passion for creative writing. After 32 years working for the Anne Arundel County School District as a speech therapist, she retired several years ago and moved to Baltimore, immersing herself in the writing of poetry.

However it wasn’t until Pitcairn’s death that Brewer’s deepest poetic passion came to life.

“I think he just had more to say and I was simply channeling it,” she told Voice of Baltimore in a recent interview, adding: “I really don’t know where the poems came from.

“I just felt, somehow, I connected with Stephen’s spirit. And you have to be careful when you talk like that, but I do [feel it]. I’m a writer and I’m very intuitive.”

Brewer began to write her initial Pitcairn poem at the request of one of her neighbors.

“My neighbor asked, ‘Do you think you could write a poem for the family because we all feel terrible about what happened to Stephen?’” Brewer said.

Pitcairn was walking north on St. Paul St., coming from Penn Station the night of July 25, 2010 after a weekend visit with his two sisters in New York, talking on his cellphone to his mother in Florida, when 37-year-old John Wagner and his 24-year-old girlfriend, Lavelva Merritt, stabbed him to death.

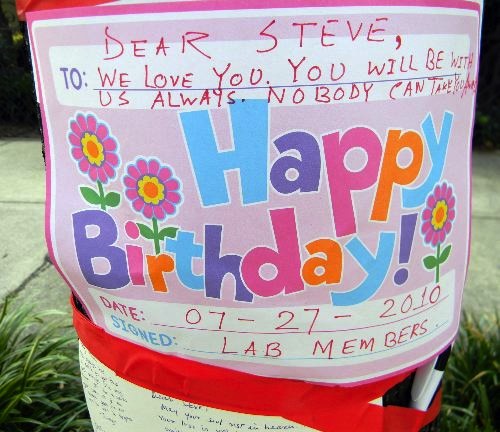

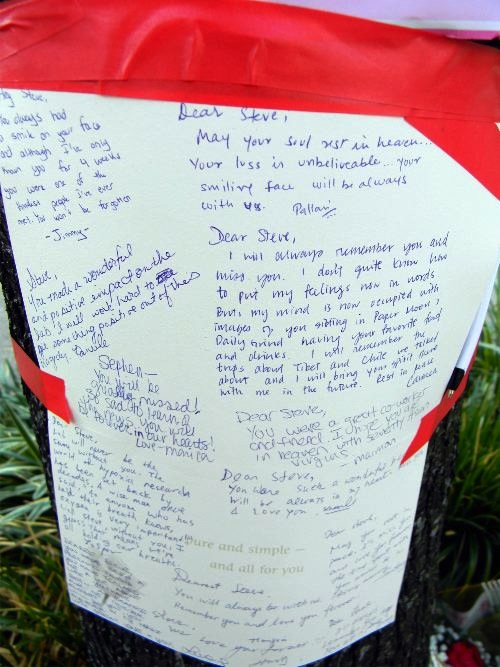

A tree adjacent to the sidewalk where Stephen Pitcairn was murdered on the night of Sunday, July 25, 2010 was adorned with remembrances two days later on what would have been the prospective medical student’s 24th birthday. Note cake at base of tree, with candle half burnt out, and Happy Birthday messages on tree trunk from friends & co-workers at the Johns Hopkins Hospital lab where he assisted with breast cancer studies. Also two unopened packages of Twizzlers (at left), Pitcairn’s favorite candy. (VoB Photo/A.F. James MacArthur)

The victim’s mother, Gwen Pitcairn, heard the murder over the phone — a part of the story that Brewer described as “unconscionable.”

“Within an hour [after Pitcairn’s memorial service] I had started to write that first poem in my own voice, expressing the grief,” Brewer said.

She then sent that initial poem, along with a letter and a sympathy card, plus a poem written by the late Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue, to the Pitcairn family, who live in Florida.

A month later, to her surprise, she received a response from Gwen Pitcairn.

“I thought, ‘My God, this woman has just lost her son and she’s taking the time to write me a thank-you note,’” Brewer said.

Around the time Gwen Pitcairn sent her letter, Brewer was writing another poem about the murder, but this time in Stephen Pitcairn’s voice.

“I was really nervous about sending it [to Gwen] because I’m writing a poem in the voice of her son, and I didn’t know her son,” Brewer said.

“When you write in someone’s voice and you don’t know that person, that’s very delicate territory that you’re treading. That could go really wrong.”

But again, Gwen Pitcairn expressed gratitude, Brewer said.

Brewer continued to send poems to Gwen Pitcairn as they were written. And in exchange, the murdered researcher’s mother sent back emails and pictures of her son, as well as articles he had written, Brewer said.

“There’s something about poetry — I didn’t know her but yet she opened up to me when I sent the poems because the poems were about her son,” Brewer explained.

“She really poured her heart out to me in those emails, so I was getting a feeling for the deep, deep sorrow — for the loss that she was experiencing.”

Brewer recalled the incident as she walked with a Voice of Baltimore reporter and editor to the site of Pitcairn’s murder, where, three-and-a-half years later a tree at the edge of the sidewalk where Pitcairn died still had a bow tied around it in his memory.

Brewer stood transfixed on the sidewalk where the murder took place and pointed out the home of Reggie Higgins, a Charles Village resident who heard the commotion between Stephen and the murderers, Brewer said.

“[He] found Stephen lying on the ground, bleeding to death,” Brewer recalled. “He just scooped [Stephen] up in his arms and held him and comforted him, waiting for the ambulance to arrive.

“But it was too late.”

Murdered Johns Hopkins researcher Stephen Pitcairn, shown here with the daughter of his host on a visit to Japan approximately 2 years before his untimely death, when he was a junior in college.

Pitcarin was killed just two days before his 24th birthday, she said.

And Higgins was so deeply affected by the murder that he left Baltimore and moved back to his native state of North Carolina.

The outpouring of emotion Brewer felt from the community and the Pitcairn family subsequently inspired her to write more poems about the murder, in various voices.

“There’s a poem in Gwen’s voice,” she explained; “a poem in Reggie’s voice; and there’s a poem in which the moon speaks, the tree speaks, and a poem in which the knife speaks,” Brewer said.

Apprentice House publisher Kevin Atticks, whose Loyola University Maryland student publishing house published After Words, described Brewer’s poems as “different, yet compelling” because he had never before read poetry that stemmed from inanimate objects.

“I decided the knife should speak,” Brewer explained, “because at the murder trial John Wagner did not apologize for the killing — he said he didn’t do it.

“So, I had the knife apologize to the family in the poem.”

Within two years, one poem led to a total of 13, and in February 2013, After Words was published by Apprentice House, the nation’s first and only book publishing organ run entirely by college students.

According to Atticks, Apprentice House had not previously published a lot of poetry, but decided to publish After Words because it focused on a specific incident that happened in Baltimore.

Atticks added that books are very two-dimensional, but that After Words left him with “a 360-degree perspective” of what happened the night of the murder.

It was the trial — described as a “very disturbing and unnerving experience” by Voice of Baltimore’s managing editor, AL Forman — that gave Brewer the idea for her book’s title.

“Going to that trial, it was all these words,” Brewer explained, questioning: “After the words, what happens then?

“So, After Words just seemed to be the right title to me.”

Shirley Brewer signs copies of her book of poetry, After Words, at the Ivy Bookshop in Mount Washington. Photo of Stephen Pitcairn, whose July 25, 2010 murder down the street from Brewer’s home is the subject of the book, is at right. (VoB Photo/Bonnie J. Schupp)

Brewer’s words — “one knife and we all bleed” — sums up how one tragic incident can be felt by so many. Still, many people have apparently found peace of mind from reading After Words.

“In a strange way, Shirley’s poems seem to make sense of what many have called a senseless crime,” Forman said. “And I would hope that anyone — especially those living in the Charles Village community — would find some sense of comfort from reading Shirley’s work.”

After a reading at the Baltimore Book Festival last September, Brewer said she approached two women from New York City who she saw purchase her book.

“[One of the two women] told me that her 20-year-old son had been stabbed to death,” Brewer said.

The woman then told Brewer that for 10 years she had been trying to find words to express the immensity of her loss and had only just then found them in the pages of After Words.

Forman described Brewer as “a ‘speaker for the dead,’ giving voice to one who can no longer speak for himself.”

He and Brewer first met at Wagner’s trial, which Forman chronicled for VoB. He was struck by Wagner’s “perpetual state of denial,” he said, “to the extent of claiming at his sentencing, à la O.J. Simpson, that ‘the real killers are still out there somewhere’ and that Baltimore police have been remiss in not looking harder for them.”

The book includes not only Brewer’s poems, and a dedication written by Pitcairn’s mother, but also the slain researcher’s medical school essay: he was hoping to one day become a doctor, so that he could help people.

Stephen Pitcairn in Japan. The slain Johns Hopkins research- er’s 2010 murder in the 2600 block of St. Paul St. in Charles Village is the subject of poet Shirley Brewer’s book of verse.

“Writing does heal,” Brewer said. “Everyone’s been through something, and people don’t know how to begin to write about sad things.

“They want to go there,” she explained; but in a contradictory sense, they also “don’t want to go there.”

Brewer’s earlier published work includes A Little Breast Music — an assortment of free-verse poems about family and loss, with humor in the work. She has also had numerous poems published in a wide variety of literary journals and anthologies.

She hopes that people who read After Words and are so moved will contribute to Stephen Pitcairn’s scholarship fund.

According to a Johns Hopkins University website, “The Stephen Pitcairn Scholarship Fund was established at the School of Medicine to honor Pitcairn’s work at the Institute of Cell Engineering.”

Brewer described her book as “pure elegy, with very spare language.” She added that she had never written anything like After Words before.

“To this day, it’s one of those miracles. I don’t know where the poems came from,” she said.

“I didn’t set out to write this book…

“But it happened, and I’m glad.”

sheilm1@students.towson.edu

A.F. James MacArthur and VoB Managing Editor Alan Z. Forman contributed to this report.

READ VOICE OF BALTIMORE COVERAGE OF THE PITCAIRN MURDERER’S TRIAL: click here

…AND SENTENCING — HE RECEIVED THE MAXIMUM ALLOWED BY LAW — by clicking here.

Editor’s note: The Pitcairn murder case became an issue in the election campaign for Baltimore state’s attorney during the summer of 2010 when challenger Gregg L. Bernstein chastised then-City State’s Attorney Patricia C. Jessamy for failing to prosecute repeat offenders like Wagner and allowing them to roam the streets to rob and kill.

Bernstein defeated Jessamy and is now Baltimore City State’s Attorney.

In a statement following Wagner’s sentencing, Bernstein said his office continued “to express our deepest condolences to the Pitcairn family and all of Stephen’s friends. While the verdict and sentence cannot bring him back, we hope that his family and friends will find some measure of closure in the result.”

Regarding the “memorial tree” in the 2600 block of St. Paul Street, A.F. James MacArthur, who photographed the display exclusively for Voice of Baltimore in July 2010, said at the time he could not “remember ever seeing one of these [memorials] for a white guy. Typically,” MacArthur noted, “whatever the race, in Baltimore, this stuff is usually only seen deep in the ‘hood.’”

A birthday card signed by ‘Lab Members’ with the inscrip- tion, ‘Dear Steve, We love you. You will be with us always. Nobody can take you away,’ and including a dozen person- al notes was displayed on what would have been Stephen Pitcairn’s 24th birthday, July 27, 2010, on a tree adjacent to the sidewalk in Charles Village where the Johns Hopkins cancer research assistant & med school aspirant was stab- bed to death. Also attached to the tree were two photos of Pitcairn, and at the base was a birthday cake with a candle on it half burnt out, along with two bouquets of flowers.

Pitcairn ‘memorial tree’ was photographed by A.F. James MacArthur exclusively for Voice of Baltimore in July 2010.

January 27th, 2014 - 1:01 PM

[…] extreme. But at this time in my life, I am fortunate enough to write for the Voice of Baltimore (http://voiceofbaltimore.org/archives/11591) and sing with the country-rock band Denim ‘N’ Lace […]

September 9th, 2025 - 8:58 AM

[…] Archive “after WORDS” — Speaker for the Dead -.” Voiceofbaltimore.org, 1 Jan. 2014, voiceofbaltimore.org/archives/11591. Accessed 13 Mar. […]