HONOR & RECOGNITION

FOR HIS INTEGRITY

Political world today would be more civil

if 38th Vice President had won in 1968

OVERWHELMED BY NEGATIVITY,

VOTERS SOLD HUMPHREY

AND THE U.S. SHORT

By David Maril

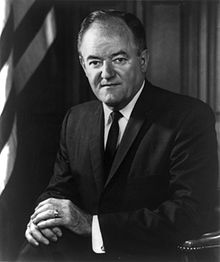

I was too young to vote but memories of Hubert Humphrey losing to Richard Nixon in 1968 are still fresh in the mind.

While books, documentaries, and news/talk programs are focusing on the 50 year-anniversaries of John F. Kennedy’s assassination and Lyndon Johnson’s launching of his Great Society programs, Humphrey’s importance should not be overlooked.

In today’s world of political rancor, with character assassination and demonizing replacing civilized and rational debate, Humphrey’s influence on history remains relevant and is growing.

With him, it has become a case of what might have happened and how different our world and political outlook would have been if Democrats and liberals hadn’t been so hardheaded, petty and dysfunctional in 1968 when he lost to Nixon.

And I am as guilty as anyone. If I could have voted in that election, I probably would have skipped the balloting or written in Eugene McCarthy’s name in protest.

In the eyes of us peace-marching college kids and antiwar liberals, Humphrey, in 1968, seemed nothing more than a stooge for Lyndon Johnson and his quagmire war policy. We mocked Humphrey’s cheery demeanor as being out of touch.

We laughed at Humphrey apologists at the time who defended him as a man of loyalty and honor, carrying, as the vice president, the burden of Lyndon Johnson’s escalating Vietnam War.

Years later we learned that Humphrey had consistently, behind closed doors with Johnson, spoken out against escalating the war. It was also revealed he had been threatened by LBJ he would not get the party’s support if he used an antiwar theme in his presidential campaign.

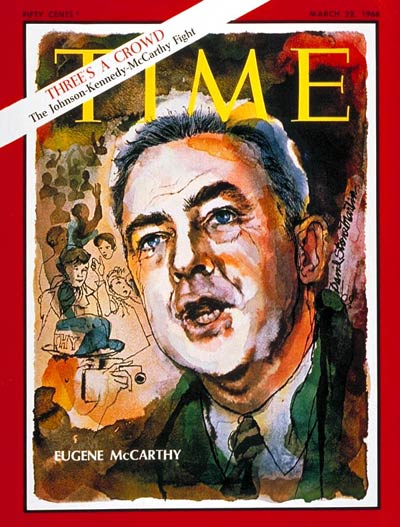

Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy ran for Democrat- ic nomination for president in party primaries of 1968.

“Clean” Gene McCarthy had courageously tested the early primary waters against Johnson and rather surprisingly drew enough support to drive LBJ, who had won a landslide victory in 1964, into seeking retirement.

Despite an unimpressive record on domestic issues, McCarthy caught the fancy of idealistic, young voters. If we’d done our homework, we’d have seen that except for the Vietnam War, McCarthy was anything but a liberal while Humphrey had been fighting the good fight for progressive government and Civil Rights for decades.

When Robert Kennedy, encouraged by McCarthy’s early primary showing, belatedly entered the campaign, emotions simmered and the demand for peace grew stronger. The tone shifted from negativism and being anti-government to hope for positive change.

But when Kennedy was assassinated in California, after winning that state’s primary just as his campaign seemed to be gaining momentum, the mood of unrest and bitterness returned.

If Robert Kennedy hadn’t been assassinated, he may very well have won the Democratic presidential nomination. One certainty is that as toxic as the Democratic Convention was in 1968 in Chicago, it would have probably been even more divisive with Kennedy and McCarthy wrestling over the antiwar voters and Humphrey representing the party establishment.

And McCarthy wouldn’t have backed off and thrown his support behind Kennedy to unify the peace movement. He was not, as he demonstrated during the election, a team player.

Humphrey, who won the party nomination, would have been better off not attending the Democratic Convention, which became little more than a military camp. Humphrey’s detrimental link to the unpopular Johnson seemed even more pronounced as he accepted the nomination while antiwar protesters and the Chicago police waged war in the streets.

Many followers of Kennedy and McCarthy were unwilling to accept Humphrey’s nomination and support him. A large number of Kennedy supporters in fact were so disillusioned by the senseless murder of their candidate, they remained in a bitter state of mourning.

It was as if Humphrey had somehow played a role in Kennedy’s death. McCarthy’s lack of enthusiasm backing Humphrey, a fellow Minnesota Democrat, was also an important factor that boosted Nixon.

Richard Nixon is sworn is as 37th President of United States, March 20, 1969. Outgoing Vice Pres. Hubert Humphrey stands behind Nixon, at right. Nixon’s wife Pat holds Bible.

Even many liberal democrats who couldn’t stand the sight of Nixon decided it really didn’t matter who won between the two candidates. In another election at any other time they would have been working overtime on Humphrey’s campaign, trying to get him elected and Nixon defeated.

When Humphrey finally began speaking out against the war, Nixon’s lead started to evaporate. If the election had been held a few weeks later, he probably would have won, the final vote was that close.

It’s funny how one’s perspective can change. Watching a recent PBS documentary examining Humphrey’s impressive career, it’s painfully obvious to me now there was a distinct choice in that 1968 election.

It was a terrible mistake for so many people, who actually shared Humphrey’s progressive political philosophy, to write him off. Surely many, to this day, regret not getting out to support and vote for him. Under Nixon, the Vietnam War actually expanded before finally coming to an end.

While George Washington is called the Father of Our Country, Nixon could rightly be labeled the Father of Dirty Modern Politics. We can perhaps give Nixon credit for helping establish the lack of decency that characterizes our political world today.

If Humphrey, a highly ethical public servant with the principles so missing from most elected officials “serving” us today, had won, the world would be a much different place. He was a positivist and a man of vision.

Some cynics mocked his ebullience, his exuberant cheerful demeanor. But the truth is he was a genuine, principled individual who raised the standards of politics. We could certainly use more statesmen like him today.

Humphrey’s defeat by Nixon should serve as a continual warning: Campaigns fueled by negative emotions focusing on a single issue seldom produce constructive results.

We need rational, big-picture-thinking political leaders who put a value on finding common ground. These days, there’s too much babbling and not enough listening. Our elected officials repeat memorized talking points and ignore pressing and legitimate questions.

Much of this sorry, modern political climate took root back in 1968, when so many voters were too blind to see there was a difference between Humphrey, an honorable public servant, and Nixon, who ended up resigning in disgrace.

davidmaril@hermanmaril.com

“Inside Pitch” is a weekly opinion column written for Voice of Baltimore by David Maril.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. was the 38th Vice President of the United States, serving a single term from 1965-1969 under President Lyndon Johnson.

After losing the presidential election of 1968, the former Mayor of Minneapolis, who had been a pharmacist early in his career and three-term United States Senator from Minnesota, returned to the Senate in 1971, where he served until his death seven years later in January 1978.

When Humphrey was elected Vice President in 1964 he was succeeded in the Senate by Walter Mondale, who served as Vice President under Jimmy Carter and lost his own presidential bid, to Ronald Reagan, in 1984.

CHECK OUT LAST WEEK’S “INSIDE PITCH” COLUMN: click here

…and read previous Dave Maril columns by clicking here.

March 10th, 2014 - 7:38 PM

[…] Voice” for the original program. CHECK OUT LAST WEEK’S “INSIDE PITCH” COLUMN: click here …and read previous Dave Maril columns by clicking […]