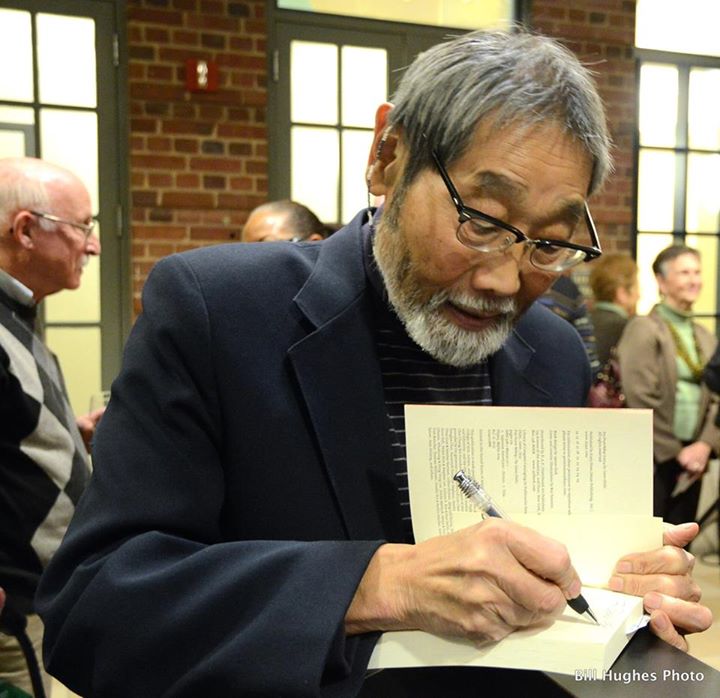

Gene Oishi autographs his autobiographical novel, Fox Drum Bebop, at Mount Washington Conference Center. (VoB Photos/Bill Hughes)

GENE OISHI WAS NINE YEARS OLD

WHEN HIS AMERICANIZED FAMILY

WAS INCARCERATED BY THE U.S.

Suffered trauma in adult life as result

MAIN CHARACTER IS AUTHOR’S ALTER EGO

By Alan Z. Forman

Former Baltimore Sun reporter Gene Oishi’s premiere novel, Fox Drum Bebop, offers a fictionalized account of the emotional and psychic repercussions of the Japanese-American experience brought on as a result of his forced incarceration by the U.S. Govern- ment in the Arizona desert during World War II.

Oishi is now 81 years old and this is his first publication, other than short stories, of a fictionalized account of what it means to be Japanese in America, based on his own life experience.

He, his parents and 120,000 other Americans of Japanese birth or descent living on the West Coast of the United States were rounded up and sent off to government-run internment camps following the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces.

However the novel is not Oishi’s first attempt to tell his story in book form. That came with In Search of Hiroshi, an autobiographical memoir he wrote in 1987 and which became a basis for Fox Drum Bebop.

Hiroshi Kono, a fictional reporter for the Baltimore Herald newspaper (read: Baltimore Sun), is based on Oishi himself, although the author maintains that while “my family and I served as models for the fictional Kono family and Hiroshi, we are different.

“The Oishis are not the Konos, and I’m not Hiroshi,” he says, despite the identical name used for his 1987 memoir — which began as a novel but morphed into a work of nonfiction when he discovered that the factual telling of his personal story precluded any leaps into the world of imagination and he “had to give up the pretense that it was a work of fiction.”

Fox Drum Bebop is his attempt “to tell a story that was bigger than myself, to tell a tale about the Japanese in America….

“Hiroshi is my fictional alter ego who appears in nearly all of my short stories,” he explained in an email interview with Voice of Baltimore.

‘THE BOY I USED TO BE’

“In my memoir, In Search of Hiroshi, he is the boy I used to be before the war — happy, secure and unashamed of being Japanese….

“Before the war, I was perfectly comfortable with being both Japanese and American. It was not a matter of choosing sides, but of finding a balance between the two.

“The war changed all that.”

The difference, he explained, “between reality and fiction is that reality is chaotic, it doesn’t have to make sense and usually doesn’t.”

As a journalist therefore, in order to be honest, he had to present facts in a way that was supported by evidence, clearly identifying speculation and opinion as such and not presenting them as anything more.

However “a novelist is not restricted in that way,” he explained. The novelist “can let his imagination run free and create whatever story he wishes — but the story he tells, unlike journalism, has to make sense, it has to be coherent.”

“Every successful work of fiction, whether it is a short story, novel, play or movie, has to have a satisfying narrative or emotional arc, and at least a momentary sense of completion.”

‘THE CHALLENGE A NOVELIST FACES’

“So that’s the challenge a novelist faces that a journalist doesn’t.”

Oishi has been working on the novel “for half a century,” he told a book-launch gathering last week at the Mount Washington Conference Center in Northwest Baltimore, explaining that he had been “in denial” for years following his three-year incarceration that ended with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Japanese surrender in August 1945.

“Only after I got over my deep denial, I began to understand how traumatized I had been,” he said. Oishi was nine years old when the forced confinements began and he first started to question, albeit subconsciously, who is allowed to be “American.”

It was “ruinous for my parents, split my family, scattered them,” he said.

His family was split up in the camps, his father at one location for the first two years; Oishi, his mother and sister at another. After graduating from high school, his sister got a scholarship while in the camp and was permitted to go to college in Minnesota.

His oldest brother was sent to a different camp because, like their father, he was suspected of having pro-Japan sympathies.

Two other older brothers were serving in the U.S. Army. Both graduates of Stanford University, they were in the Military Intelligence Service, which provided translators and interpreters for the Army in Asia.

CELEBRATED 442nd REGIMENTAL COMBAT TEAM

In the novel, one of the brothers serves with the celebrated 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a nearly all-Japanese-American unit that fought primarily in Europe beginning in 1944 and which was one of the most decorated units in U.S. military history, having been awarded eight Presidential Unit Citations.

Its motto was “Go for Broke” and 21 of its members were awarded the (Congressional) Medal of Honor for their service to America during World War II, despite the fact that many of their families back in the States were interned.

One of those Japanese-Americans in the 442nd who was awarded the Medal of Honor was later-United States Sen. Daniel K. Inouye of Hawaii, who lost his right arm to a German grenade, yet refused evacuation and continued to direct his platoon until enemy resistance was broken and his men could be deployed in defensive positions.

In Doris Kearns Goodwin’s study, No Ordinary Time (a 1995 history chronicling the lives of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt that focuses particularly on the period between 1940 and FDR’s death in 1945), the First Lady’s belief that Japanese-Americans were deprived of their civil liberties by the United States is discussed at length.

Mrs. Roosevelt helped in small ways wherever she could, such as making certain that the medals of Japanese-American soldiers, specifically those serving in the 442nd Regiment, were pinned on their mothers’ blouses while they were in internment camps and their sons were fighting the war in Italy, Southern France and Germany.

“The father in Fox Drum Bebop is modeled after my own,” Oishi explained in an email following the book launch last week.

His father “was a leader in the Japanese community and never hid his pro- Japan sentiments,” Oishi said.

“Japanese as well as all non-white immigrants were excluded from American citizenship by law,” he explained. “In many western states, ‘persons ineligible for citizenship’ were banned from owning real estate, entering into long-term lease agreements, and denied licenses to engage in some professions.

“Most if not all Japanese immigrants thought of themselves [as] subjects of Japan and hoped one day to return to their homeland.”

As such, neither of Oishi’s parents was a U.S. citizen in the summer of 1942 when the family’s internment began. In his formative years the family had spoken only Japanese at home — it was Oishi’s “first language” then — but upon entering school, “English became my first language,” he said, and his Japanese language skills quickly fell by the wayside.

“I didn’t speak English when I entered kindergarten,” he added, “but when I think back on that time, I am amazed at how quickly English became my first language, and how easily Japanese language and culture began fading into a secondary and later vestigial role.

“As I grew into school age, I became American. How could I not? surrounded as I was by the culture of American public schools, by movies, by TV and radio shows, newspapers, magazines, comic books.”

He does not speak Japanese at all today.

However he doesn’t “bother [now] to say I’m Japanese-American — I say I’m Japanese,” like most other Americans whose families emigrated to this country.

Still, on recent visits to Japan, “it was a thrill to walk down streets with people that looked like me.”

‘THE IDEA OF BEING JAPANESE’

“The idea of being Japanese affects me emotionally,” he explained.

His high school years were “the most miserable time of my life,” he said, adding that he is convinced “there are two kinds of people — those who enjoyed high school and those who didn’t.”

However it was only after reaching adulthood that he began to realize how traumatized he had been by his family’s incarceration in the internment camps.

“The war didn’t come as a complete surprise to the United States,” he told Voice of Baltimore in a subsequent interview.

“The FBI, the Office of Naval Intelligence and the State Department had investigated Japanese communities in the United States months before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“They had made up lists of those who might be security risks in the event of war with Japan. On the so-called ‘A list’ were community leaders, prominent farmers, businessmen, Buddhist priests, Japanese language teachers — those espousing Japanese culture and values and any who openly presented themselves [as] patriotic subjects of Japan.

“My father, a community leader in the small farming town of Guadalupe, Calif., was on that ‘A list.’ Two FBI agents came to our house within hours of the Pearl Harbor attack and arrested him.

“In my novel, the father of the family is also arrested the night following the attack on Pearl Harbor,” he noted.

ON THAT SO-CALLED ‘A LIST’

Approximately 2,000 Japanese were on that so-called “A list” and were arrested soon after the war began, and the rest of the Japanese-American community, “some 120,000 of us,” he said, “were shipped to concentration camps in the months following.

“The question is, Did we truly pose a threat to national security?

“The Justice Department, including the FBI, didn’t think so,” Oishi maintains, “nor did the Office of Naval Intelligence.

“There were a small number of German nationals arrested and detained…, but most of them were given hearings and released. There was no thought given to any mass incarcerations of persons of German or Italian ancestry,” despite the German-Italian alliance early in the war.

“In 1983, a study commission created by Congress concluded that the incarceration of Japanese-Americans had not been justified by military necessity… [and] that the decision to incarcerate was based on ‘race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership,’” he said.

Then in 1992, 47 years after World War II ended, Oishi and his mother each received reparations in the amount of $20,000 as a result of the initiative of now-deceased U.S. Sens. Inouye and Spark Matsunaga, both of Hawaii, both Japanese-American.

Terming the $20,000, “compared to the offense… insignificant,” Oishi noted that the overall cost to the U.S. Government was over $1 billion, and that the monetary payout “to back up the apology by the government meant a lot to me.”

TURNS HIMSELF INTO A SAMURAI

As for the book’s title, the novel was originally called “Bread Crumbs,” which is now the title of Chapter 4. “Fox Drum” refers to a Japanese legend in which a fox turns himself into a samurai and whose skin later becomes the skin of a drum.

“Bebop” relates to the main character’s musical interests. In the novel, as well as in real life, Oishi played trombone in an American Army band in Verdun, in Northeastern France, as well as in an enlisted men’s jazz club.

His hero Hiroshi is “a tormented soul” who has not learned the valuable lesson that Japanese-Americans are “real people with all the virtues and vices, strengths and weaknesses, wisdom and foolishness, intelligence and stupidity that are common to all of humanity,” Oishi notes.

“At the same time, most of us are different in unique ways from other Americans, and there is nothing wrong with these differences.

“They make us who we are.”

alforman@voiceofbaltimore.org

EDITOR’S NOTE: Fox Drum Bebop was published by Kaya Press, an independent not-for-profit publisher of Asian and Pacific Islander diasporic literature, founded in 1994 and dedicated to the publication of new and innovative fiction, poetry, critical essays, art, and culture, and the recovery of important and overlooked works from the Pacific Rim and the API diaspora. It will be available on Amazon.com next week (Nov. 30th) and may be purchased locally at the Ivy Bookshop — www.theivybookshop.com — Falls Road at Lake Avenue in Northwest Baltimore.

November 24th, 2014 - 11:16 AM

Good job, Al. You covered all the bases and more.